Sleep, Simplified: A Practical Guide for People Who Are Tired of Being Tired

For those who are tired of being tired.

Over the years, one relationship I have had ups and downs with is sleep. I can pass out on a jet plane with chaos everywhere, but if there is one small disturbance in my room at night, I am instantly on edge and wide awake. The worst is when I know I need to sleep because I have a big day tomorrow, and my ADHD brain decides it is time to fire on all cylinders.

If you can relate to any of that, you will probably find at least one of the methods below useful. You do not need to do all of them. Pick a few, run them consistently for 10 to 14 days, then reassess.

Take it easy on yourself. Do not pressure yourself to fall asleep. If you are anxious about a big day tomorrow, or you just have a lot on your mind, that is normal. We all live busy lives. Try to layer a few of these techniques into your sleep routine and do not expect them to work instantly. Everyone is different, so experiment and see what actually works for you.

One thing I want you to keep in mind is that falling asleep is not like flipping a switch. It takes time. Be patient with it. Treat this like training. Consistency wins, and it pays off over time.

Listen to your body

This one gets ignored the most.

If your brain is shutting down at 8 pm and you’re forcing yourself to stay up because “it’s too early,” that’s counterproductive. Sleep is driven by a mix of sleep pressure and your circadian rhythm, and when those line up, there’s a real window where falling asleep is easier (Borbély, 1982). Miss that window and you often get a second wind, driven by alerting signals from your circadian system, which can leave you wired for hours even though you’re clearly tired (Dijk & Czeisler, 1995). This happens more often after heavy training weeks or mentally demanding stretches, when recovery needs are higher.

Yawning, zoning out, and losing focus aren’t weaknesses. They’re signals. When that real sleep wave hits, take it. Don’t fight it and don’t negotiate with it. Ignoring those cues delays sleep onset and shortchanges recovery when your body is actively asking for it.

Listening to those signals becomes much easier when your sleep schedule is consistent.

Keep Sleep & Wake Times

Your body runs on a built-in timing system called your circadian rhythm. Think of it as your biological clock. It regulates when you feel awake or tired, hormone release, body temperature, energy levels, and recovery. Your brain thrives on predictability. When you go to bed and wake up around the same time each day, your body starts preparing for sleep before you even lie down. When those times are all over the place, it creates a low-grade version of jet lag, even if you haven’t traveled.

This is why consistency matters. Falling asleep gets easier. Waking up feels less brutal. Big swings in sleep and wake times confuse the system and make both ends harder.

If you had to pick just one thing to lock in, consistent wake-up time matters more. It acts as the anchor for your circadian rhythm. If you have a late night, still get up at roughly the same time and aim to go to bed earlier the following night. Locking in both bedtime and wake time is ideal, but life happens. The anchor is what keeps things from spiraling.

Most people obsess over sleep duration. While that matters, research consistently shows that regular timing is more powerful long term than chasing hours alone.

One important note for shift workers or night owls: banking sleep can help. Extending sleep in the days before a stretch of short or disrupted sleep has been shown to improve alertness and performance during night work. It’s not a perfect fix, but it’s a useful tool when you know a tough block is coming (Cushman et al., 2023).

How to apply this in real life:

Step 1: Pick a wake time you can keep

Choose a wake time you can hit seven days per week within about 30 minutes. This is your anchor.

Step 2: Hold it for 10–14 days

Even if sleep feels rough at first, still keep the wake-up time consistent. This trains your clock.

Step 3: Build bedtime backward

Start with roughly eight hours as a baseline and adjust based on how you feel.

Step 4: Fine-tune

If you’re lying awake forever, push your bedtime later by 15–30 minutes.

If you’re crashing early and waking too soon, shift bedtime earlier by 15–30 minutes.

Step 5: Use light properly

Morning light tells your body it’s time to be awake. Dimming lights at night helps signal that sleep is coming. Kill overhead lights, keep things calm, and let your nervous system downshift.

If You Are Tossing & Turning

If after about 15 to 20 minutes you are just lying there tossing and turning, get up. Go read a book on the couch or do something genuinely relaxing. Then return to bed when you actually feel sleepy again. Lying in bed stressing about the fact that you need to sleep is not going to make you fall asleep. All it does is teach your brain that bed equals frustration.

Do not watch the clock. Estimating time is good enough. Watching the minutes tick by just adds fuel to the fire. Your bed should be only used for 2 things: the birds & bees and SLEEP. If your brain associates it with anxiety or doom scrolling then it makes falling asleep and staying asleep that much harder. This is called stimulus control and its very powerful tool for training your body to know when to sleep. It's so effective it's been proven to be an effective method in treating insomnia believe it or not (Demers Verreault et al., 2024).

Switch The Mindset

A tactic that has worked well for me is changing how I approach sleep. Instead of trying to force sleep and lay there wide-eyed. I use effective tactics to switch my mindset without consciously making the decision to switch into sleep mode. I focus on relaxing my body and letting my brain slow down. It might sound silly, but it beats relying on sleep meds long term and dealing with their side effects (Zee et al., 2023).

Two tools that are simple and effective.

Gratitude list

Pick three things you are grateful for that day. Do not overthink it. No, it does not need to change every night. The goal is to pull your brain away from problem solving and threat scanning, and into something calmer.

Think about how those things make you feel fortunate for what you have, not just that they exist.

1.

2.

3.

Body scan or sleep meditation

If your brain will not shut up or your body feels restless, a body scan or sleep meditation can help bring your nervous system down a notch. This is not about knocking yourself out. It is about creating the conditions where sleep can happen. Here is a playlist with a few solid options to get started. Pick a voice that calms you. Everyone is different.

Caffeine Cut Off

This is non-negotiable if your sleep sucks.

Caffeine has a half life of roughly 5 to 7 hours. A half life just means the time it takes your body to clear half of a substance.

Example.

You have 200 mg of caffeine at 2 pm.

Around 8 to 9 pm, about 100 mg is still in your system.

Around midnight, roughly 50 mg is still hanging around.

That is basically full coffee floating through your system while you are trying to sleep.

This is where people say, “Caffeine does not affect me.” Sure, it might not stop you from falling asleep. But it can still reduce deep sleep, increase nighttime awakenings, and keep your nervous system more alert than you realize (Gardiner et al., 2023).

In most cases, following a caffeine cut off helps more than it hurts. So instead of arguing with it, give it a proper run.

Rule

Stop caffeine 8 hours before bed. If your sleep still feels light or broken, make it 10–12 hours.

Worst case, nothing changes. Best case, your sleep quality improves more than you expected.

Common sources of caffeine

Obvious ones.

Coffee & espresso

Energy drinks

Pre-workout

Matcha

Tea

Sneaky ones.

Diet Coke and many colas

Decaf coffee, which still contains some caffeine

Dark chocolate and chocolate based protein snacks

Kombucha, which varies by brand

Some pain relievers or headache meds with added caffeine

If you are struggling with sleep and still having these late in the day, this alone might be the issue.

Alcohol/Marijuana

This is about balance, not perfection.

Alcohol can make you feel sleepy and help you fall asleep faster. That is why a lot of people use it at night. The problem is what happens once you are actually asleep. Research shows that alcohol leads to more wake ups during the night and reduces REM sleep, which is the stage of sleep that helps with memory, mood, and feeling mentally sharp the next day (NIAAA, 2023; He et al., 2019; Roehrs & Roth, 2018).

This is where balance matters. One drink earlier in the evening, especially with food, is very different from several drinks or drinking right before bed. Having a drink once in a while is unlikely to ruin your sleep long term. Drinking more often, drinking more than one or two, or drinking late at night usually shows up as lighter sleep and feeling less recovered the next day (Roehrs & Roth, 2018).

Marijuana works in a similar way.

THC can help you relax and feel drowsy before bed, which is why it feels helpful in the moment. But research shows that it changes how your sleep cycles work. It tends to reduce REM sleep and disrupt the normal pattern of deep and light sleep through the night (Babson et al., 2017; Gates et al., 2014).

Short term, it might feel like you slept deeper. Over time, regular use is linked to poorer sleep quality overall. When people cut back or stop using it, vivid dreams and more wake ups are common. That is not your sleep getting worse. It is your brain getting back to its normal rhythm (Bolla et al., 2008).

This is not an all or nothing conversation. Using alcohol or marijuana once in a while is very different from consuming it on a regular basis. The more you rely on something to knock you out, the more it can quietly mess with how well you actually rest.

If sleep is a priority right now, this is a lever worth being mindful of. Not perfect. Just intentional.

Napping & Sleep Inertia

Naps can help, but they can also backfire. Sleep inertia is that groggy, foggy feeling right after waking up. It usually fades, but longer or poorly timed naps can leave you feeling worse for hours and interfere with nighttime sleep (Tassi & Muzet, 2000). Short naps earlier in the day, around 10–30 minutes, tend to improve alertness while minimizing sleep inertia, whereas longer naps increase the chance of that heavy, sluggish feeling (Lovato & Lack, 2010). If you consistently wake up from naps feeling wrecked, that is useful feedback and a sign they are not helping your recovery.

A strong alternative is NSDR (non-sleep deep rest). It allows the nervous system to downshift without actually falling asleep, which avoids sleep inertia altogether. Guided NSDR and similar relaxation-based practices have been shown to reduce fatigue and improve perceived recovery without disrupting sleep later on (Moszeik et al., 2020). This became a go-to tool for me when I was working in a clinic. Even 10 minutes between clients was enough to reset and feel sharper going into the rest of the day.

Device Interruptions

If your phone is buzzing, ringing, or lighting up at night, your nervous system stays on alert whether you consciously notice it or not. Research shows that smartphone notifications can trigger a stress response similar to a low-grade fight-or-flight reaction, increasing physiological arousal even when the phone is not actively used (Kushlev et al., 2016; Thomée et al., 2011). You can imagine how repeated micro-alerts like that fragment sleep and make it harder to fully downshift overnight.

The fix is not willpower. It is the environment. Put your phone on Sleep Mode or Do Not Disturb. Most smartphones let you customize this so only true emergencies get through. When it is set properly, people messaging you can usually see that your phone is on Do Not Disturb. That is intentional. Decide ahead of time what actually counts as an emergency and mute the rest. If your phone is allowed to interrupt you at night, your sleep never fully gets a break.

Iphone Customize Do Not Disturb Android Customize Do Not Disturb

Room & Environment

Your sleep environment matters more than most people think.

A cool room helps your body do what it naturally wants to do at night. Core body temperature drops as part of the sleep process, which is why sleeping in a cooler environment tends to support deeper, more stable sleep (Kräuchi, 2002; Okamoto-Mizuno & Mizuno, 2012). Cool does not mean uncomfortable. If you wake up sweaty or buried under blankets like you’re in an oven, that’s a problem. The same idea applies to food. Heavy or spicy meals close to bedtime raise core body temperature and keep digestion working overtime, which can delay sleep and reduce sleep quality (St-Onge et al., 2016). Spicy food has its benefits. Just save it for earlier in the day.

Light control is huge. Light is the strongest signal telling your brain when to be awake. Exposure to light at night, even from small sources, can delay melatonin release and fragment sleep (Chang et al., 2015). Blackout curtains or a sleep mask are simple fixes if your room gets hit with streetlights or early sunrise. On the flip side, if you wake up in darkness, especially in winter or darker climates, bright light in the morning helps shut off sleep signals and get your system moving. Blackout curtains are great for controlling timing. Morning light is what flips the switch back on.

Noise matters if you’re sensitive to it. Travel taught me this fast. Even if noise doesn’t fully wake you up, it can pull you into lighter stages of sleep and reduce overall sleep quality (Basner et al., 2014). Earplugs or noise-canceling headphones can be a game changer. If you can sleep through a thunderstorm, congrats, skip this part. Most people can’t.

Finally, aim for the same sleep setup as often as possible. This one isn’t always easy, especially when traveling, but it works. A familiar bed, pillow, and general setup act as cues that tell your brain it’s safe to shut down. When I was on the road, my top priority was always a decent bed and pillow. If you’ve got that, you’re laughing. Your brain loves familiar cues, and consistency makes falling and staying asleep easier.

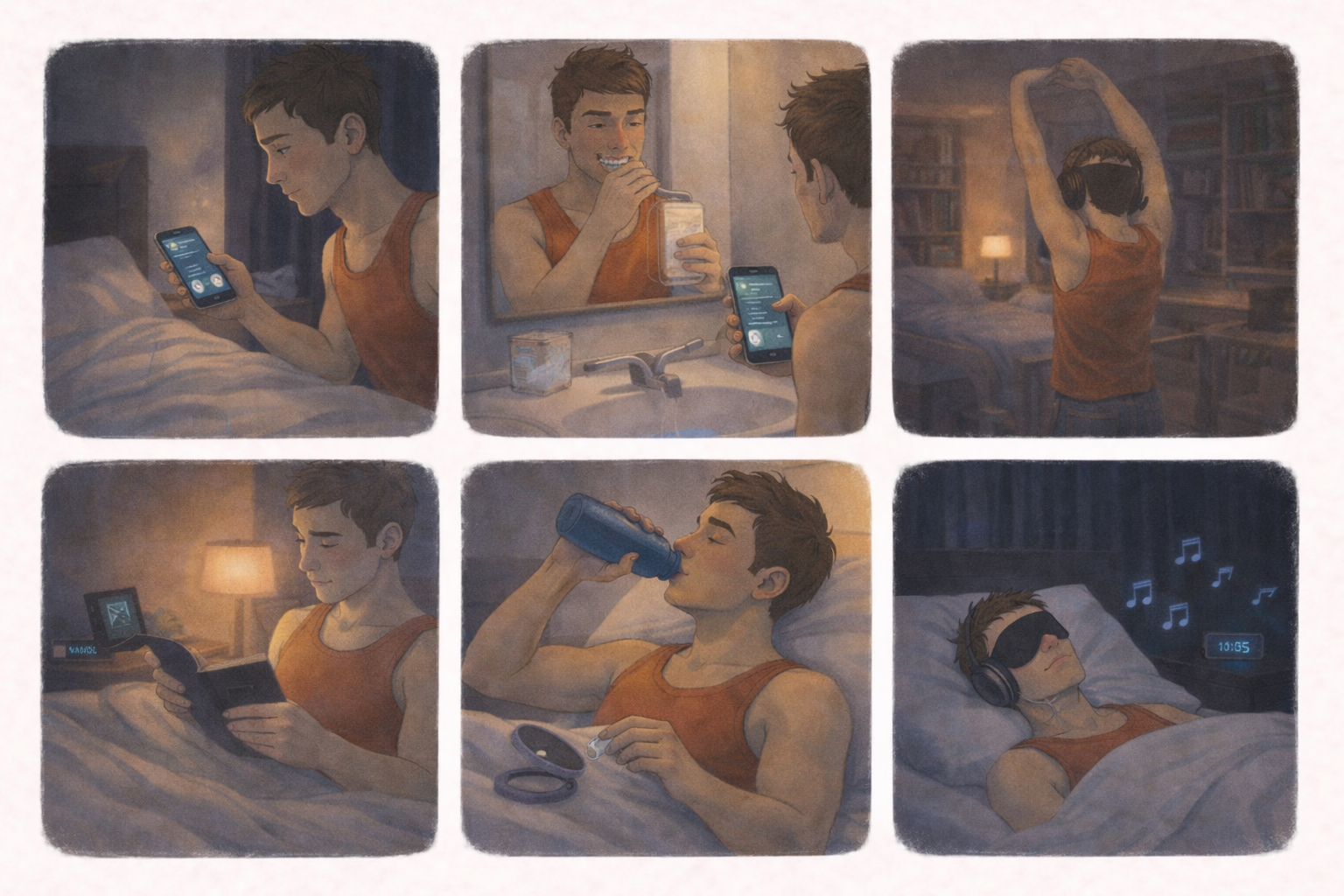

Bedtime Routines

Even if you are not tired yet, the routine itself helps flip your body into rest mode. Here are my personal at home routine & my travel routine.

Home Routine

Morning

Open eyes and turn off the morning alarm.

Don’t use my phone till I am fully out of bed.

Open shades to allow natural light in or turn on bright light.

Throw on some clothes and chug some water.

Restrict caffeine intake for 90 mins (avoids my mid day crash).

Take out my retainer and splash my face with some cold water.

Evening

Brush and floss, clean retainer and have it ready.

Stretch for 10 to 15 minutes with controlled breathing.

Send any final texts or do a last phone check before turning on Sleep Mode.

Practice French on a language app while stretching to distract my brain.

Dim lights and remove blue light from the room.

Read a book or Kindle on the lowest brightness with night mode on.

Read until tired. Sometimes it is one page, sometimes it is thirty.

Lights off, retainer in, chug some water. Settle in for a deep, restful sleep.

Travel Routine

Morning

Open eyes and turn off the morning alarm.

Don’t use my phone till I am fully out of bed.

Throw on some clothes and chug some water.

Allow natural light in or ideally go ground my bare feet and take in the sun.

Restrict caffeine intake for 90 mins (avoids my mid day crash).

Take out my retainer and splash my face with some cold water.

Evening

Plan the next day, then leave it alone. No revisiting.

Lock up gear and confirm all belongings are accounted for.

Post stories or update loved ones and then put the phone on Sleep Mode.

Get into bed with a journal/book, headphones, and eye mask ready.

Write, draw, or take brief notes about the day using a blue-light filter if I’m on my phone.

Read until genuinely tired.

Headphones on, sleep audio if needed.

Eye mask on. Lights out. Chug water then sleep.

If you’ve made it this far into the article, take 10 minutes to write down your own bedtime routine and put it into practice. Don’t expect it to work perfectly the first time. Make small tweaks until it works best for you and your environment.

Full Body Stretch Routine (Bonus)

Timing guidelines

Single-leg movements: 30–40 seconds per side

Bilateral stretches: 45 seconds to 1 minute 30 seconds

Purpose

The goal here is to tap into your parasympathetic nervous system, the part of your nervous system responsible for rest and relaxation.

How to approach it

Start each stretch with deep, slow breaths if it feels intense.

Let your eyes rest or close.

As you settle into the position, switch to controlled nasal breathing.

Think about the muscle relaxing rather than forcing the stretch.

Let your joints soften and your heart rate slow down.

Move slowly between stretches. This is not about flexibility. It’s about downshifting.

Downward dog single leg calf stretch- 30-40 sec perside

Figure 4 crossover stretch- 30-40 sec perside

Seated forward fold- 1 min

Couch stretch- 30-40 sec perside

Layback quad stretch- 1 min

Pigeon pose- 30-40 sec perside

Supine leg crossover- 30-40 sec perside

Bed lat stretch with Frog- 1 min

Tadpole Stretch- 1 min

Savasna pose (box breathing 4-4-4-4)-1:30-2 mins

References

Basner, M., Babisch, W., Davis, A., Brink, M., Clark, C., Janssen, S., & Stansfeld, S. (2014).

Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health. The Lancet, 383(9925), 1325–1332.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61613-X

Borbély, A. A. (1982).

A two-process model of sleep regulation. Human Neurobiology, 1(3), 195–204.

Chang, A. M., Aeschbach, D., Duffy, J. F., & Czeisler, C. A. (2015).

Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(4), 1232–1237.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1418490112

Cushman, P., Scheuller, H. S., Cushman, J., & Markert, R. J. (2023).

Improving performance on night shift: A study of resident sleep strategies. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 19(5), 935–940.

https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.10642

Demers Verreault, M., Granger, É., Neveu, X., Pizzamiglio Delage, J., Bastien, C. H., & Vallières, A. (2024).

The effectiveness of stimulus control in cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Journal of Sleep Research, 33(3), e14008.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.14008

Dijk, D. J., & Czeisler, C. A. (1995).

Contribution of the circadian pacemaker and sleep homeostat to sleep propensity, structure, and EEG slow waves in humans. Journal of Neuroscience, 15(5), 3526–3538.

Gardiner, C., Weakley, J., Burke, L. M., Roach, G. D., Sargent, C., Maniar, N., Townshend, A., & Halson, S. L. (2023).

The effect of caffeine on subsequent sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 69, 101764.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101764

Kräuchi, K. (2002).

How is the circadian rhythm of core body temperature related to sleep regulation? Clinical Neurophysiology, 113(10), 1505–1516.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1388-2457(02)00173-9

Kushlev, K., Proulx, J. D., & Dunn, E. W. (2016).

Silencing your phones: Smartphone notifications increase inattention and stress. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(7), 893–900.

https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000170

Lovato, N., & Lack, L. (2010).

The effects of napping on cognitive functioning. Journal of Sleep Research, 19(2), 249–257.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00781.x

Moszeik, E. N., von Oertzen, T., & Renner, K. H. (2020).

Effectiveness of relaxation techniques on fatigue, stress, and recovery: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4784.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134784

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2023).

Alcohol and sleep.

https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-and-sleep

Okamoto-Mizuno, K., & Mizuno, K. (2012).

Effects of thermal environment on sleep and circadian rhythm. Journal of Physiological Anthropology, 31, 14.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1880-6805-31-14

Roehrs, T., & Roth, T. (2018).

Sleep, sleepiness, and alcohol use. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 39(1), 53–61.

https://arcr.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-and-sleep

St-Onge, M. P., Ard, J., Baskin, M. L., Chiuve, S. E., Johnson, H. M., Kris-Etherton, P., & Varady, K. (2016).

Meal timing and frequency: Implications for cardiovascular disease prevention. Advances in Nutrition, 8(2), 213–231.

https://doi.org/10.3945/an.116.013771

Tassi, P., & Muzet, A. (2000).

Sleep inertia. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 4(4), 341–353.

https://doi.org/10.1053/smrv.2000.0098

Thomée, S., Härenstam, A., & Hagberg, M. (2011).

Mobile phone use and stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression among young adults. BMC Public Health, 11, 66.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-66

Media / Tools Referenced (Non-Academic)

Huberman Lab. (n.d.). Non-sleep deep rest (NSDR) [YouTube video].

https://youtu.be/u0U9z5hvx-A

Huberman Lab. (n.d.). Yoga nidra for recovery [YouTube video].

https://youtu.be/IS5gUUxv5HY

Spotify. (n.d.). NSDR / Yoga Nidra playlist.

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/4YRmX3ZkB8HUVPBDBJbiQV